Hey there,

I met Peter through this newsletter with him being a reader. We ended up talking on the phone one day and then we’ve kept in touch throughout the last few months. Peter has a wealth of knowledge about the chemical industry and synthetic polymers.

Peter started selling specialty polymeric films and sheets in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean, co-founded a polymers distribution company that was acquired by GE plastics in the 1990s and was the director of marketing for American Mirrex. Peter would go on to later found Montesino for providing expertise in polymers in packaging to companies such as AbbVie, Vlariant, Pfizer, Honeywell, and Takeda. Peter was also the founder and president of the Society of Plastics Engineers in Puerto Rico.

Lately, our conversations have been focused on the industry’s history and its current lack of penchant disrupting itself. I think there are some companies out there trying to do new things such as corporate venture capital in addition to traditional R&D, but I think there is also quite a bit of pressure to extract as much money out of the industry in the short term with little to no desire to invest for the next century.

Here are Peter’s thoughts on where the industry is currently with some light editing by myself. The questions at the end are things I ponder all the time. Let us know what you think in the comments.

Tony

A Tale of Two Stories

Different sides of the same coin

By Peter Schmitt

The Plastics Story

This fairy tale story begins with the discovery and development of synthetic polymers. As Tony Maiorana notes, chemical technology and polymer chemistry were crucial parts of the development of “modern” society.” They took off in the early 1900s with Bakelite or phenolic resins and then “hit the accelerator with polyethylene and nylon” (Tony Maiorana, The Polymerist). These early “plastics” offered revolutionary properties, enabling the creation of entirely new products with never-before-seen performance and affordability. This period was driven by a spirit of progress and a focus on meeting societal needs through innovative materials. In short, a fairy tale that had no downsides or limit to where the story could take us.

Between and after two world wars, plastics production ramped up at an extraordinary speed, driven by a mix of military and consumer demand. The story shifted towards large-scale production, cost reduction, and exceptional profitability. Design focused on convenience and disposability, leading to significant waste generation and pollution. These factors were magnified when looking at engineering-grade materials (fluoropolymers, etc.), where huge increases in productivity and massive cost cuts were achieved, while waste management and disposal were not on the “critical path.”

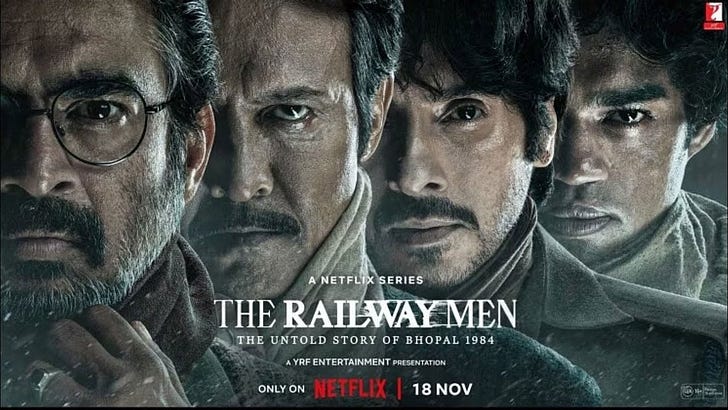

The Plastics Story is often told through the taglines of this period: DuPont’s “Better Living Through Chemistry, “The Miracles of Science,” and Union Carbide’s “A Hand in Things to Come” exemplify it. However, accidents and incidents in the chemical and plastics industries challenged that the miracle narrative—that these advancements don’t come without costs. DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane), Love Canal, Dioxin Incidents, and the Bhopal disaster brought waste, contamination, and safety issues to the consumer public’s consciousness. The companies responsible for these types of massive environmental pollutions and disasters no longer exist in the way they did before their respective disasters. Union Carbide lost control of methyl isocyanate in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India and it resulted in the worst industrial disaster the world has ever witness. The explosion killed at least 2,259 people and affected over 500,000 more through exposure to methyl isocyanate (very toxic). Netflix dramatized Bhopal in The Railway Men.

Union Carbide had a history of poor safety and killing people before Bhopal. Carbide asked miners in West Virginia to mine silica without masks and the miners developed silicosis with a death toll of 476 people. Carbide also mined asbestos in King City, California that it sold to its employees and eventually became a superfund site. Dow Chemical would eventually buy Union Carbide after the Carbide sold off all the profitable parts of the company to pay off debts. While polymer development continued to offer new discoveries and materials that met the original story’s metrics of performance and affordability, the fairy tale nature of the plastics story came with nightmares. The accumulation of pollution eventually became so apparent that it was impossible to not notice, and it has taken longer to clean-up than anyone could have ever anticipated.

At least we created some shareholder value, right?

The Green Story

Here, the story begins with collective efforts to protect the environment and ensure its sustainability for present and future generations. The “Green” story moved through Conservation, Pollution Control, Sustainability, and Social Justice, and in recent decades, has “gone global.” It looked not only at chemicals and plastics immediate impact on the environment, but at their feedstocks such as crude oil. Activism accelerated rapidly into class action suits looking for multibillion dollar settlements after incidents like Love Canal and Bhopal and feedstocks started to become a concern during the Arab oil embargo in the 1970s. Academic chemists started to believe that the very innovations responsible for the nightmares described above could also be the thing that saved us from ourselves.

PFAS and The Downward Reactive Spiral

Hiroko Tabuchi’s articles in The New York Times (May 28th and June 10th) illustrate the situation today. In the first article, a well-known law firm urges the industry to prepare “for a wave of lawsuits with potentially astronomical costs” that will dwarf past asbestos settlements. On June 10th, Tabuchi noted that the American Chemistry Council and the National Association of Manufacturers sued the federal government over “a landmark drinking-water standard that would require cleanup of so-called forever chemicals linked to cancer and other health risks.”

To date, the Chemical and Plastics Industries use two strategies: one “reactive” - such as the lawsuit against the EPA, and the other “proactive” - such as the promotion of physical and chemical recycling, some voluntary phasing out of PFAS materials, some work at cleanup, some limited attempts at remediation.

This lawsuit is the latest in “a downward reactive spiral” that polarizes people according to their views, such as pro-business versus pro-environment, rather than focusing on the problem. A class action defense can lead to an additional downward spiral of negative publicity about the industry and damage to brands. The history to date does not speak well for reactive spirals: 3M and DuPont settlements are currently in the tens of billions, most consumers see both nanoplastic particles and PFAS materials in their blood and talk about switching to using glass and metal containers only.

A Lesson from the Catholic Church?

This a good time for the Chemical and Plastics Industries to pause and look at recent history. The Catholic Church followed a “reactive spiral” strategy for decades. The result to date: a large transfer of wealth to attorneys and countless bankruptcies. Far worse for the Church was the loss of trust, especially at the higher levels of the institution. The legal tactics employed to try and limit financial liabilities actively contributed to the destruction of the public’s trust in the Catholic Church. The preference for “reactive” strategies marked “a race to the bottom.”

Reactive Spirals and the Destruction of Trust

Reactive Spirals consist of four steps:

Initial Action: An initial action or policy by one party triggers a response from another party. This action might be seen as threatening, unfair, or aggressive, leading to defensive or retaliatory measures.

Response: the second party perceives the initial action as harmful or threatening and responds with an action intended to counter or punish the initial party. This response often exceeds the original action in severity.

Escalation: Each subsequent action becomes more aggressive or defensive, with each party trying to outdo the other. This leads to a cycle of retaliation that escalates the conflict.

Entrenchment: As the conflict escalates, each party becomes more entrenched in their positions. Compromise becomes difficult, and the conflict becomes more intense and destructive.

Many companies today, when facing class action lawsuits, focus solely on minimizing immediate costs. This strategy has long-term repercussions. The deterioration of consumer trust impacts customer retention, market differentiation, competitive advantage, and positive regulatory support. If the reactive spiral continues to damage consumer trust, the use of chemicals and plastics can implode. Today the public’s perception of the chemical and plastics industry story moved from “the excitement of making good things for life” to “It’s everywhere. I need to escape it or it will help kill me.”

A Generative Spiral

There is a third option: a generative response. This echoes the original spirit of innovation seen at the birth of the plastics industry, where solving problems and meeting needs of customers and consumers drove profits. This approach fundamentally rethinks and redesigns processes and products to positively impact society and the environment If the industry commits to regeneration and solving new problems then new profit sources and improved performance can emerge. Transformative change not only addresses current crises but also prevents future ones and enhances overall sustainability. This requires significant investment, a readiness to learn from mistakes, and patience. In essence, we need not just new leadership within the industry that represents 25% of US GDP, we need investors in this space who are more willing to take on informed risks.

Generative Spirals require trust. Given past damage created by the class action lawsuit-settlement battles, this remains a major challenge for the industry.

What is the right channel to restore a common sense that new products and processes will be affordable and improve the environment and our health?

How do the Chemical and Plastic Industries regain the trust of the consuming public?

The downward reactive spiral of litigation and lobbyists is not that channel.

If you want to contact Peter Schmitt please do so at peter.schmitt@montesino.com or through this consulting firm Montesino

This is an excellent article. It captures much of what I have found to be frustrating on the part of corporate behavior, not just in chemicals/plastics. The offer to create a "generative" solution is also welcome and really should be more of a common sense approach. Companies really don't seem to learn from past mistakes which, in the case of trying to sell solutions like chemical recycling, seriously undercut their credibility with the public. The same is true with industry associations. Their complete and utter tone-deafness to anything other than the profitability of their members (and therefore association dues) renders their opinion 1-sided and not credible in the eyes of the public.

Going one step further - and offering another analogy to the Catholic Church - we could look to South Africa's "Truth and Reconciliation" process as a model for achieving generative solutions. I'm sure the legalese would be brutal, but it might offer a starting point.

An earlier version wrongly attributed "better living through chemistry," to Dow.

It was originally developed for DuPont.