Note: Origin has sponsored this newsletter in the past, but they are not sponsoring or paying me to write this post. Actually, no one but the readers are supporting me right now (people at Origin read this newsletter too) or until I get another monthly sponsor.

Is This Pricing Model Working For Everyone?

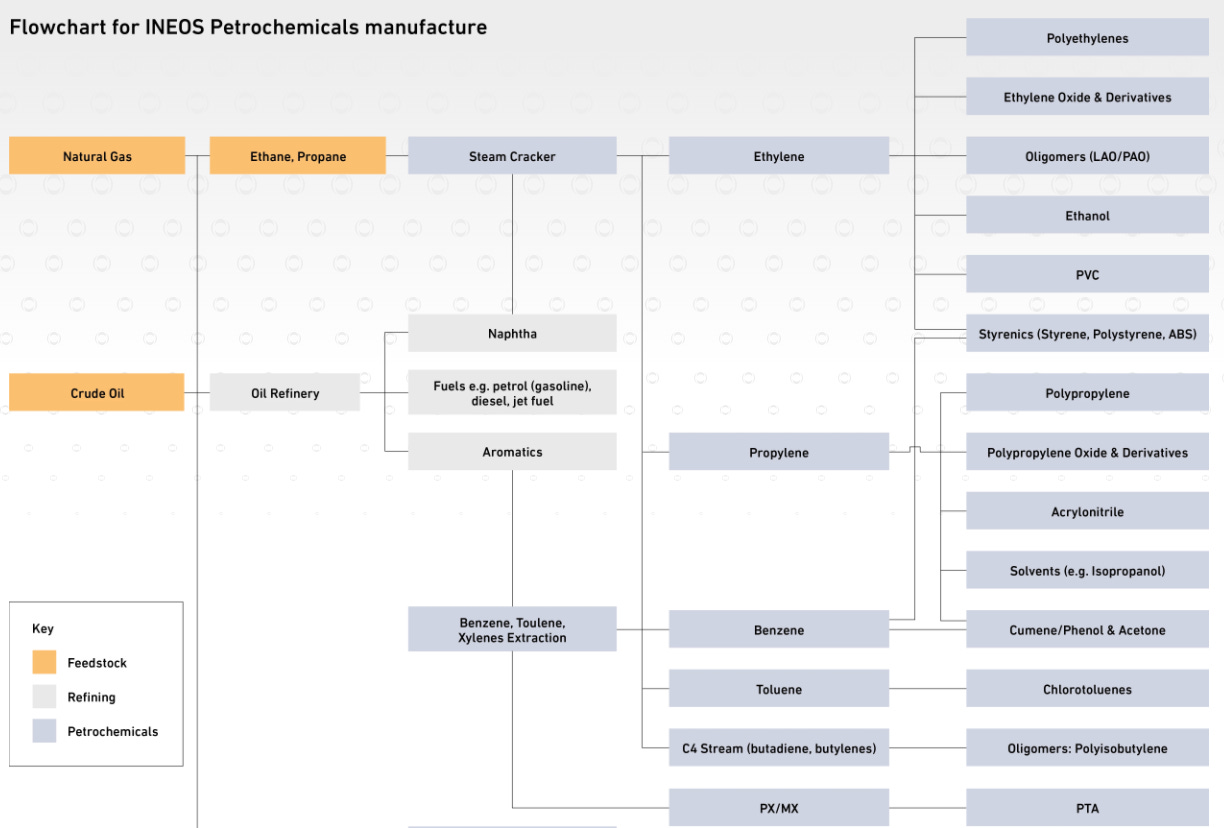

When I think about our global economy I view things through the lens of being a polymer chemist. I see synthetic polymers everywhere and I usually can trace their provenance back to crude oil. Our modern world is built on the foundation of fossilized carbon and it’s been relatively accessible. Chemists and chemical engineers have given society the ability to unlock enormous productivity from the different fractions of crude oil.

Advances in chemistry, polymers, and chemical engineering have given us tires, cable insulation, anti-corrosion coatings, durable adhesives, insulation, paved roads, tape, and so much more. The oil and gas industry supplies the chemical industry with the requisite feedstocks to create the stuff that we rely on everyday and integrated oil companies like ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell also play in the chemicals space themselves. As the chemical and oil industries grew in parallel, the chemical industry became dependent on fossilized carbon as a feedstock.

Since the chemical industry is reliant on oil this means the prices of chemicals ultimately fluctuate with the price of oil. When oil prices are high there is a flurry of activity of price increases and then when oil prices fall there the prices go back down (eventually). We are only able to view the prices of chemicals as a derivative of oil. The price of oil is the floor of chemical pricing. The best margins a chemical company can hope to gain is somewhere around 20-25% (EBITDA) for the most specialized operations or the most disciplined six sigma commodity organizations.

We are stuck on oil because it’s easy and what are our alternatives?

There have been a lot of companies that attempted to make commodity chemicals and polymers from sugar and have a viable business–Bioamber is a good example. Elevance was doing something similar with fats (I think they are in trouble) and Doris of Green Chemicals blog has a comprehensive update here. The issue in starting with relatively refined biobased molecules like sugars and fats is that they have to be grown using land suitable for agriculture.

In the event you haven’t noticed the current ongoing war in Ukraine has the potential to seriously disrupt agriculture supply chains through a number of different routes. The first being that Russia and Ukraine account for a significant amount of wheat exports globally. Ukraine accounts for about 10% of global wheat production and Russia accounts for 18%. The second pathway is that Russia exports a large amount of natural gas to western Europe and this natural gas is used for numerous energy needs, but it also powers the production of synthetic fertilizer via the Haber-Bosch process. To make ammonia (used in fertilizer) the first step is making hydrogen via steam reforming of methane (natural gas) and then reacting hydrogen with nitrogen in the presence of a catalyst with a lot of heat (also produced via natural gas). If you want a good place to start diving deep into ammonia this is a good start. Natural gas it turns out is used to do a lot more than power heating furnaces.

High prices for staples such as wheat, corn, and fat means that the companies utilizing these food resources as feedstocks for chemical production also have to compete with hungry people. The situation in the short term around food scarcity might not be improving anytime soon. Daniel Maxwell writes the following for The Conversation:

As of April 8, the average cost of staple food grains had jumped by more than 17% from February levels. For food-importing countries everywhere, this increase will push the cost of food significantly higher. And with the war likely to continue, a global supply shortfall could lead nations to adopt measures such as export bans that further distort food markets.

If we as a society had to choose between feeding people and making chemicals I think the choice is obvious–we feed people. We also have a better choice for biomass to make chemicals. Lignocellulose.

What Is Lignocellulose?

Cellulose is the most abundant biomacromolecule on the planet. Lignin is the third most abundant biomacromolecule on the planet and they often come together in the form of plants. If we think about all of the available biomass in the world there is abundant lignocellulose from grasses to trees to corn stalks. The only problem is that lignin and cellulose often come together in the form of lignocellulose.

Paper producers have long figured out how to get the cellulose separated from lignin and hemicellulose through various chemical methods such as soda and sulfite which can be both water and energy intensive. All the paper and cardboard we use went through a pulp mill at one point. Lignin has often been the byproduct from pulp mills and in its raw form it’s often referred to as “black liquor.” Lignin once it has been removed from the water can either be burned to produce energy for the pulp mill. Fully dried lignin costs about a dollar a pound last I checked via Ingevity.

The joke has often been in the biobased chemistry and materials community is that you can make anything from lignin except money. I’ve tried numerous times to use lignin as a chemical building block in graduate school and in the chemical industry. I even wrote about it here. Apparently some companies are making advances in the area such as UPM for wood adhesives used in plywood.

When it comes to making chemicals, DuPont sold their cellulose to ethanol plant a few years ago, but overall the push has been to make biofuels and not anything else. How would we even start to realize making chemicals from lignocellulose though? That is what Origin Materials is doing.

Origin Materials

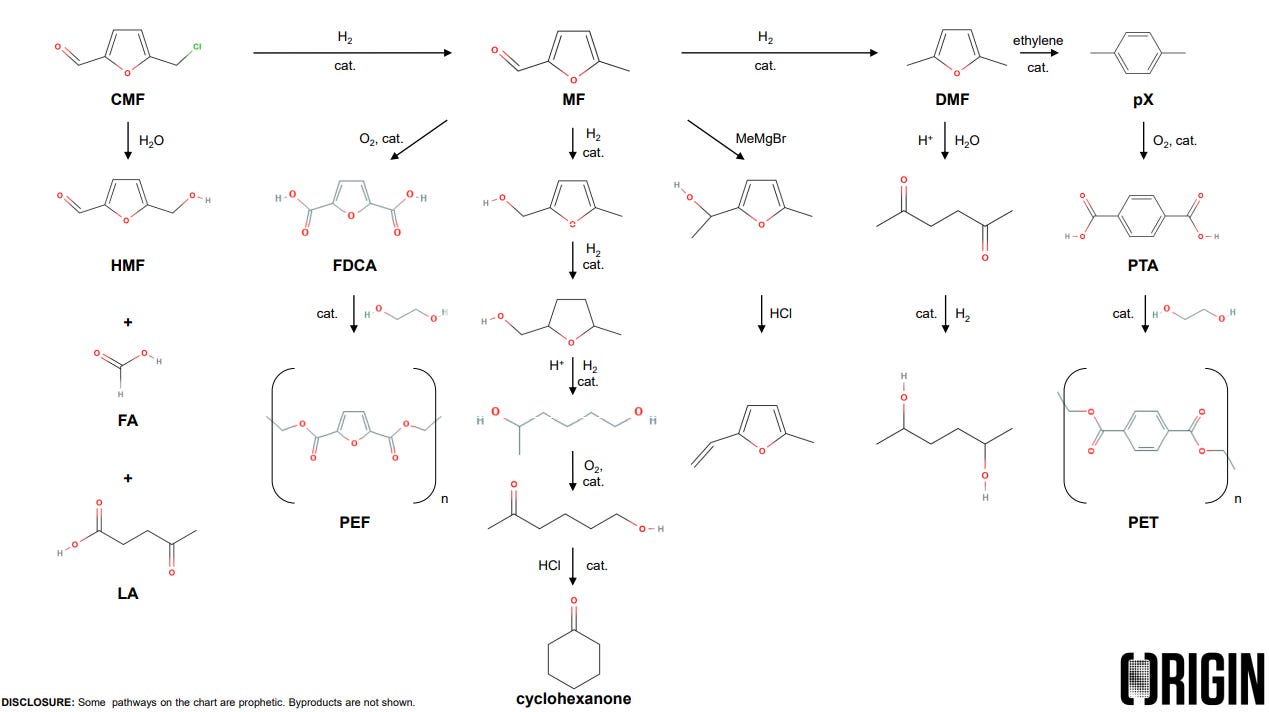

At the most fundamental level Origin Materials is transforming wood chips or other lignocellulosic biomass into chloromethyl furfural (CMF) through acid hydrolysis, which they hope to sell as a platform chemical into the chemical industry. The first use for chloromethyl furfural is to get to para-xylene, the precursor to para-terephthalic acid, a building block for polyethylene terephthalate (PET). The demand for sustainable PET has been exploding recently with prices of recycled PET surpassing the prices for virgin as demand increases in both packaging and apparel.

During my conversation with John Bissell, the co-CEO of Origin Materials, the opportunity that Origin was sitting on became quite clear. The majority of pricing on chemicals is due to supply, demand, and raw material costs and as I’ve explained above those raw materials are often based on crude oil. In comparison to crude oil on a weight basis wood chips could be 3-5 times cheaper than oil. Using CMF to make para-xylene and ultimately terephthalic acid should in theory be more cost efficient through the wood chip route.

To compare Origin’s acid hydrolysis method let’s look at Gevo’s fermentation route. In a paper in 2014 the authors estimated that Gevo’s route to para-xylene was about $4127 when starting from starch. I’m not exactly sure what the going price on para-xylene is right now, but my searching tells me it was $804/ton in 2021. Gevo’s fermentation process is way too expensive if they want to be competitive. Even a green premium wouldn’t be able to cover that sort of cost mark-up.

John expects Origin to be able to sell their para-xylene at competitive rates to the current market. To me, this indicates that Origin’s costs are likely lower or significantly lower than that of their petroleum based competitors. Origin is a public company so we should be able to see their profitability once their plants are fully operational, but if they can show that making chemicals from lignocellulose is both feasible and more profitable then I suspect investors and other companies will be trying to get into the market as well.

I had originally thought Origin Materials was going to be a PET company, but John envisions it more as a upstream chemicals producer that sells CMF and some of its derivatives. The para-xylene avenue has secured off take agreements from companies like Danone, Nestle, Pepsi, and a lot more to the tune of $5.6 billion. In a sense they are selling out their plant before it’s even finished.

Origin cannot do it alone though and they have struck up partnerships with companies such as Mitsui, Minafin, and Kolon Industries to name a few. Actually converting para-xylene to terephthalic acid is somewhat trivial. Indorama does it at scale everyday. About 20% of all the PET bottles in the world are made by Indorama. It doesn’t make sense for Origin to try and compete with Indorama, but it does make sense to supply them with sustainable feedstock that can be converted.

I think Origin Materials might be better viewed as the INEOS of biomass. They might supply the commodity chemicals, but it will ultimately be their customers who end up making the stuff we touch and use everyday. A good example might be Avantium, who is trying to commercial polyethylene furanoate, but they have to make all of their own feedstocks as well as do the polymerizations. Origin could in theory make FDCA from CMF and supply it to Avantium.

That’s the big unlock I see here. Origin has figured out a way to shortcut themselves to cost competitive biobased chemicals and they are enabling a “guilt-free” supply chain.

There is this idea that our personal choices can really impact how the world operates. If we just try and bike more, use less stuff, buy less stuff, be more mindful, recycle more, work from home, compost our food scraps, and buy electric vehicles that somehow if enough of us do it we will make a difference. Our personal actions will collectively add up over time and if we can hit a big enough scale where people act together it will be even more impactful, but the actual underlying economy of goods that we buy are set-up under the pretense of cheap and readily available crude oil.

Our choices matter to some extent, but it’s not like we have a lot of options. I think most people, if they have the money, will choose the more sustainable option, which is a marketing play on guilt, privilege, and access. Instead of having the option to choose, I think it’s even more powerful to just change the whole supply chain of how we get things as well as how we dispose of them.

When it comes to industrial polymers and chemicals, a story about polypropylene always stood out to me. Prior to the Phillips Petroleum catalyst and the Ziegler-Natta catalyst no one really knew what to do with propylene. It was a byproduct of steam cracking that no one really wanted until chemists figured out how to polymerize it and create an enormous amount of value and productivity for the world.

Origin has a similar byproduct situation. When they do the acid hydrolysis of lignocellulose they get their CMF, but they also get what they call hydrothermal carbon and some oil that is similar to tall oil. John tells me that the company will be self-sustaining on the sales they generate from CMF and para-xylene, but these byproducts are what really stood out to me as avenues of even more value.

Even if Origin can sell their byproduct or “co-products” at 10-30 cents a pound (asphalt prices) they are going to be making even more money by having people take away stuff that they don’t want. Those customers can then take those chemicals and materials and make something useful, the best part being that those things now come from biomass instead of crude oil.

As a professional chemist working in the adhesives space I’m definitely interested in these byproducts. I just hope they are better than lignin.

If they produce an oil similar to tall oil, that will be good news for the pine chemicals industry and for renewable diesel producers (depends on the volume). How much oil can they produce?

Would seem the pivot to biofuel on O2 phase1 is an economics one (larger upfront margin). This would make sense given that HTC and biofuel sit on the higher volume side of their output.

They recently talked of a surge of new demand for their HTC also.

I don't mind if CMF is pushed back, despite it being their bespoke selling card, as 1) it's inevitable as the pilot plant shows the stuff works, 2) bringing wider margins forward appears to be a wise choice amid a 5.5% fed funds rate and recent high TYield volatility / MOVEindex