Phenolic Resins, Circular Economy Investments, and Oil Pivots

Mergers and Acquisitions:

Hexion sold their global specialty phenolics, Hexamine, and European forest products business this week for $335 million. The combined revenue of this business was about $530 million and the majority of the business will be located in Europe. The only specialty phenolic plant in North America is located in Louisville, KY and this was the first place I worked out of graduate school. One thing I wonder about the details of the deal would be the sale of the integrated formaldehyde plants at each of their manufacturing locations. If the sale includes the formaldehyde plants this is a great buy, but I anticipate that it does not. I believe that Hexion ultimately will move towards selling portions of their coatings business and spinning out their formaldehyde business on its own. The press release can be read here.

What are specialty phenolic resins and Hexamine?

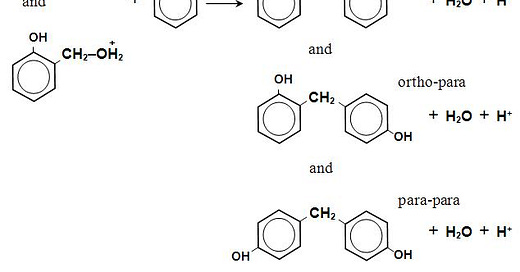

Specialty phenolics imply that there are non-specialty phenolics, but this primarily is talking about the end market of where those phenolic resins are sold, which in this case is anything but Forest Products. Engineered wood such as plywood and OSB has historically been the largest volume consumer of phenolic resin or “phenol-formaldehyde condensates,” which were invented by Leo Baekeland and were the first synthetic polymer. Phenolic resins are made by electrophilic aromatic substitution and in their uncured state are just oligomers, but once heat in the presence of a formaldehyde donor (sometimes other phenolic resins, or hexamine) is applied a very stiff chemically resistant material is produced. Hexamine is a condensate of ammonia and formaldehyde and is typically used as a formaldehyde donor.

Specialty phenolic resins get used in materials we do not interact with directly on a daily basis such as brake pads, mineral wool insulation, oil filters, bonded abrasives, refractory bricks and foundry molds (used in steel production), and as precursors for carbon-carbon composites (airplane brakes, spaceship heat shields).

The customer base for specialty phenolics should be very diverse and range from automotive, aerospace, steel, construction, abrasives, and composites. This is a solid chunk of business with a strong presence in Europe and North America. I’ll be interested to see if the new private equity partners will be able to make it even better.

Isn’t formaldehyde considered a carcinogen?

Formaldehyde is considered a carcinogen and curing or polymerizing phenolic resin results in formaldehyde to off-gas. There has been a push to regulate the emissions of formaldehyde from engineered wood where California and Europe have led the charge on reducing emissions. This has enabled new technologies to bond together engineered wood such as poly(methylene diphenyl isocyante) or pMDI. The route to pMDI involves aniline, formaldehyde and phosgene (this is why owning formaldehyde plants can be profitable). The competing technology has put a lot of pressure on phenolic resin producers that have traditionally served the forest products market and has forced some plants to shut down.

Innovation

The European Investment Bank closed a deal with Borealis and is investing €250 million (as a loan) to help create a circular polyolefin economy. Borealis is interesting because they seem to already have made significant investments into biosourced polyolefins. To recycle these polymers is possible, but there are issues of loss in mechanical properties, a clean recycling stream, and sometimes these polyolefins can be laminates of different olefins that do not mix well and thus are difficult to recycle. Diblock copolymers capable of miscibilizing two non-compatible polymers have been well studied recently and there have been further exploration of heating polyolefins under high temperature and pressure to turn them back to a semblance of their an oil distillate, which can then be turned back into ethylene. While Borealis has secured a significant amount of funding they are not alone in the pursuit of a circular polyolefin economy. The press release can be found here.

What are polyolefins?

Polyolefins broadly define a class of polymers most people consider to be plastic and typically encompasses polyethylene and polypropylene for the majority of the global volume that is produced. Polyolefins are essentially any polymer made from an “-ene” so ethylene, propylene, butene, isoprene, 1-hexene, and their mixtures. Thermoplastic polyolefins like polyethylene can be used in wire coatings, packaging, and construction products. When people talk about plastic waste they are talking about polyolefins.

Why does a circular polyolefin economy matter?

The chemical industry is aware of the effects that it has on society, both good and bad. Everyone is aware of plastic waste and the problems that it poses to society and the well-being of the planet in general. This shows that investment into new technologies can be led by a government institution by partnering with the chemical industry. Not only will new technology get developed, but it will have the chance to be deployed at scale. Most of the large polyolefin producers are already on the path to either getting biorenewable sources, figuring out ways to enable recycling, or both in the case of Borealis. This will take some time, but I believe that the chemical industry will solve the plastic waste problem. Everything wrong with the chemical industry can be fixed by what is right with the chemical industry.

Oil News

Royal Dutch Shell announced 9000 layoffs and about 1500 of them are voluntary retirements. This is a signal that the integrated oil company is looking cut costs and maybe invest more into its chemicals business as the need for oil will decrease over the next few decades. Headwinds for gasoline, diesel, and aviation fuel are being accelerated with Covid-19 travel restrictions and the rise of electric vehicles. The margins on fuels are slim and these companies rely on selling large volumes to be profitable. I expect the demand for transportation fuels to see a small resurgence as travel normalizes once a vaccine for Covid-19 is available, but once bans on new internal combustion engines start to take effect I expect the demand for fuel prices to plummet. The story from The Times can be read here.

About 91-94% of the world’s oil goes into making gasoline and other fuels while only 6-9% of global crude oil refinement goes into making chemicals.

If we stop using combustion engines completely we should have enough oil to make chemicals for a really long time—probably long enough to figure out how to grow and ferment the majority of what we need. You can’t pack an ethylene cracker on a spaceship.

The Polymerist

All of the opinions are my own and do not reflect the views of any of my employers nor are they investment advice.