The Clothing Waste Problem

Part 1: How Did We Get Here and an Interview with Dan Green of Helpsy

A few weeks ago my wife and I were going full Marie Kondo on our clothing. I have a tendency to wear my clothing to the point where people feel comfortable enough to ask me if I need some money or if I’m in financial distress. Lab coats don’t always protect your clothing the way that you would like and then the one time you don’t wear a lab coat you spill some paint or glue on yourself. Chemists still working in the lab tend not to wear very nice clothing at work for a reason.

Long story short we had a bunch of clothing that we needed to get rid of that most people wouldn’t deem fit to wear. A year ago we would have just thrown this clothing into the trash, but I knew there had to be a better way to repurpose our clothing. We searched around and eventually found a textile recycling center in our town and we donated what we thought looked acceptable (mostly not my clothing) to Goodwill.

When it comes to plastic recycling I have a pretty good idea of what is going to happen to the plastic that gets recycled. I knew less about textiles at the time, but I knew that the apparel industry many externalized costs. As I’ve written before externalized costs are good for us now in the form of low prices, but bad for us in the long run. So today I’m going to attempt to do a deep dive into textiles and I’ll talk about polymer chemistry eventually.

tl:dr

The combination of cheap labor and raw materials have resulted in the viewpoint that clothing might last us a few years and can be thrown into a landfill. We are a few steps away from treating our clothing like single use plastics.Many single use plastics can actually be used multiple times, but because the costs are so low we view them as disposable. Clothing brands are kind of like chemical companies here in that they believe it is the consumer who needs to reconcile these issues. Clothing is not trash.

Free Trade And Offshoring Light Manufacturing

A turning point in textiles in the United States happened when free trade opened up and light manufacturing left the United States for lower cost labor markets. Light manufacturing is classified as production of clothing, footwear, furniture, and other non-energy intensive goods. An old coworker of mine who is the quintessential Maine Shoe Dog. who grew up working in and with shoe factories, used to tell me stories about when he was going to China when most of the roads were undeveloped to help get shoe factories started. He knew what a Hand Stitcher (someone who hand stitches shoes) could make in a year in Maine and he knows the few people left in Maine who can still do that job. He used to travel to China for years selling products into shoe factories, but he keeps himself busy these days with the shoe manufacturing that is left in North America. When people talk about lack of manufacturing jobs in the United States a significant portion of those jobs were light manufacturing.

If we fast forward to today a significant amount of light manufacturing such as shoe and apparel production are moving out of China, where labor has experienced significant wage growth. Light manufacturing is moving to other lower cost labor countries such as Vietnam, Myanmar, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and maybe eventually even Ethiopia. The consequences of this migration of labor is that the wages are incredibly low, but have the potential to rise in some countries such as Vietnam. There is a chance to replicate what happened in China in these new developing markets. These are just some of the externalized cost of a $5 T-shirt. H&M is currently dealing with some of these externalized costs due to their contract manufacturing in Myanmar, which recently underwent a coup d'é·tat.

The concept of free trade was that it would enable lower costs for consumers in places like the US while providing better jobs to developing countries such as China. The consequences were that we reduced the number of manufacturing jobs here in the US and put the burden on people to educate themselves for jobs in the new knowledge economy. It eventually became critical to have a college degree or you were going to be left behind while minimum wage has not experienced any significant growth.

Minimum wage isn’t what it used to be. My neighbors when I lived in Louisville, KY bought their house for $4,000 about 50 years ago and its easily worth about $200,000 today. This is about an 8% compound annual growth rate over 50 years. Wage growth has not kept constant with real estate prices or public company valuations. On the other hand clothing, footwear, and electronics have all seen significant reductions in price. This sets the stage for easy consumption of depreciating assets for many people, but appreciating assets become more difficult to acquire. Another reason why Bitcoin and Non Fungible Tokens are so popular right now.

The West Wing highlighted some of the consequences of free trade episode Talking Points. I recommend watching the full episode as many of the issues outlined back then are still playing out today. Here is a clip:

Here in the United States we just witnessed four years of a nationalist president who started a trade war with China. Some people argued that the trade war was needed to bring back manufacturing jobs to the United States (easier said than done) while others argued that this tough stance was essential for enforcement of intellectual property theft and to correct the trade deficit. In reality, globalization might matter less in the future as automation of production rises. Tilman Altenburg wrote about if light manufacturing would leave South East Asia for Ethiopia in 2019 for Brookings. It might, but it is more likely that automation takes over first. Some of the most advanced manufacturing techniques in the world are being developed in China and many of the factories in South East Asia are owned by Taiwanese companies.

Even if manufacturing were to relocate back to the United States it is not so simple as just supplying jobs. I’ll always remember drinking endless cups of tea in the only air conditioned room in a factory in Vietnam while the manager of the factory yelled at my coworker in Mandarin about our product quality. Meanwhile, in the US the quality of the products we produced was considered the best for the industry that was still remaining. I think Netflix’s documentary American Factory showed how automation might just take over anyway. Here is the trailer:

Even if you can get these jobs to people in the United States I am not sure how sustainable they are unless the wages are high enough at $15/hour or $31,200/year at 40 hours a week. Housing, healthcare, and transportation costs could easily eat a $15/hour salary for breakfast and still be hungry for more. Making T-shirts and shoes has some amount of danger involved. I’ve had owners of shoe brands trying to manufacture in the United States tell me that they can’t keep labor in their factories. The workers either quit because the job is too hard or they can’t stay off drugs. Higher wages are useful, but they are only useful if costs can be decreased.

Labor is really only one part of the equation here with respect to clothing. The second part of the equation we need to consider is the raw materials that go into the textiles. Our modern textiles are primarily made from natural fibers such as cotton, hemp, wool, and silk or from synthetic fibers such as polyester, spandex, and nylon. These fibers are all biopolymers or synthetic polymers (I did say I would bring this back to polymers). Synthetic fibers really took off with the invention of Nylon in the 1930s.

Synthetic Fabrics

Synthetic polymers enabled mass production of fabrics and materials that would help American Soldiers parachute in behind enemy lines during World War II due to having nylon parachutes. Prior to nylon the only way to make parachutes was from silk, which needed to be harvested from the silk worm and required an enormous amount of labor. This is an instance where substitution of silk by nylon created a whole new industry. An equivalent in today’s terms would be software that automates workflows, which is why companies like SAP and Salesforce are so powerful.

Azo Materials has a good comparison of the differences between nylon and silk. Nylon was able to do everything that silk was able to do, but making nylon was cheaper and was more resistant to growing mildew and other microorganisms. Nylon was not only cheaper to produce than silk, but it provided more value in specific applications like parachutes. Both silk and nylon belong to a class of polymers called polyamides.

If we want to make silk we have to have a farm that incubates silk worms and the cocoons of those silk worms is where the silk is harvested. This requires significant resources in terms of raising the silk worms and the harvesting of the cocoons. The same is true of cotton farms. You need vast amounts of viable land, water, pesticides, fertilizer, labor, and equipment to just harvest cotton. Then you need more machines and water to process that cotton into yarn.

Conversely, to make some nylon or polyester you need oil refinement and a downstream oil derivatives economy that currently exists and some chemical reactors. The allure of chemistry is that what works on the milligram scale usually works at multiples of tons. The labor required to make 16 tons of nylon or polyester in a day is the same as 1 ton and the pricing of the raw materials becomes more favorable at larger scales due to favorable labor costs. Further these economies of scale became established in the 1940s and I’ve just recapped the nylon problem again. Get some chemical engineers to work at optimizing the process and eventually you can make a synthetic fiber with less raw material and land requirements than natural fibers and the process trends towards efficiency provided that the equipment is maintained. The capital expenditures might be higher be at first for synthetics, but over 10-20 years of production combined with depreciation of assets means that making nylon and polyester fibers is a great business as long as someone is buying your fiber.

But wait, there is even more value here for synthetics.

Synthetic polymers enable either mimicry of traditional fabrics and impart increased value in the form of new properties such as elasticity or breathability. There is no Lulu Lemon without Spandex, a polyurethane. There are no fire resistant suits for firefighters without Nomex, a polyaramide. There are no high performance ski jackets without GoreTex, microporous polytetrafluoroethylene. There are no Nikes without synthetic fabrics, rubber, polymeric foams, and synthetic adhesives. Prior to synthetic fabrics the best you could do if you got caught out in the rain was a rubber poncho or maybe waxed cotton while these days you could carry a rain jacket in your pocket.

Synthetic fabrics might feel like silk, soft cotton, or leather, but they can provide more value due to polymer chemists and engineers manipulating the end properties of those fabrics in a lab. There are no $15 dollar fast fashion garments without polyester and cheap labor producing cotton with minimal environmental standards in developing countries. The combination of low cost labor and low cost raw materials means we can buy new clothing every year and landfill that clothing when they start to look a little worn. Patagonia does a pretty good job outlining this on their website.

The combination of cheap labor and raw materials have resulted in the viewpoint that clothing might last us a few years and then they can be thrown away. We are a few steps away from treating our clothing like single use plastics. Many single use plastics can actually be used multiple times, but because the costs are so low we view them as disposable. Clothing brands are kind of like chemical companies here in that they believe it is the consumer who needs to reconcile these issues.

Clothes Are Not Trash

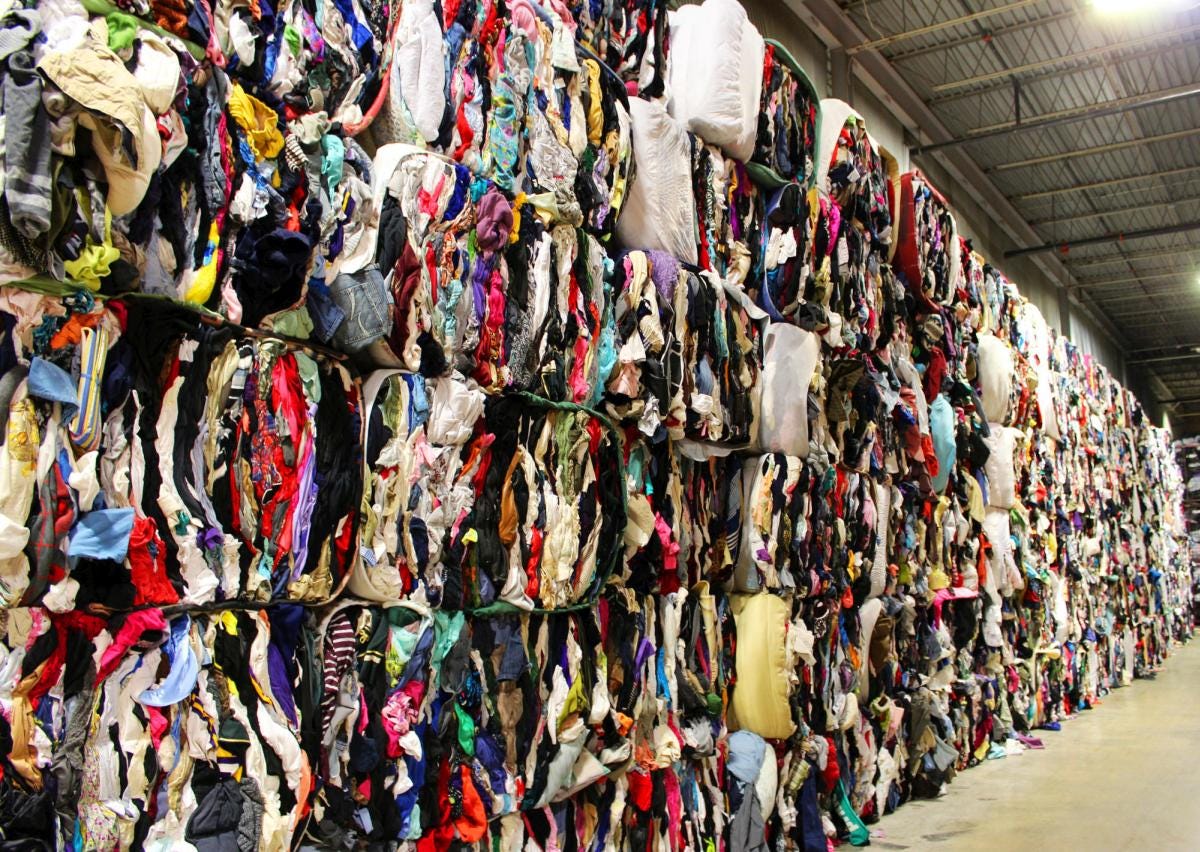

In trying to understand more about our clothing waste problem I recently spoke to Dan Green, the co-founder of Helpsy. Our conversation was too long to publish here, but he helped open my eyes to the clothing waste problem. Dan told me that the typical American generates about 100 pounds of clothing waste a year, 85% of our clothing waste goes to landfills or gets incinerated while the remaining 15% gets diverted. Of that 15% only about a quarter of it gets sold on secondary markets and the rest gets sent to developing countries such as Pakistan. That means in the US we generate somewhere close to 30 billion pounds of clothing waste every year. In the developing countries that clothing is either re-used or cut into rags. Synthetic fabrics make terrible rags so those get thrown in the trash.

Helpsy is primarily concerned about collecting unwanted clothing and trying to find a better place for them. They are a reverse logistics company in that they deal with waste as opposed to raw materials or finished goods. In their open letter to consumers Helpsy tells us:

Here are the facts: the only way recycling at necessary scale will happen is by for-profit recycling and reverse logistics companies, these companies primarily operate through bins. They afford the hefty cost of collection directly through the value of the goods collected, full-stop. Any type of recycling is a commodity-based and market-driven business. Just as in the traditional recycling industry (plastic/glass/paper), the value of the goods collected [is] in the value of the most sellable materials. Think of it this way: we can’t recycle your ripped towels if we don’t also get your Nikes. As businesses we might be able to handle damaged or defective clothing items but can only afford to do so based on the best, most reusable & recyclable items we receive.

Companies like Helpsy make money and pay their employees and shareholders much in the way of being a gold prospector. They have a massive amount of raw material that could contain “gems” and the finding and selling of those gems is what also enables them to recycle the ripped and stained underwear. A gem is a colloquial term that thrifters or pickers call rare items such as Van Halen tour t-shirts, a Burberry bag, or limited edition Nike shoes from 1995. These gems can be flipped on the internet anywhere between $200-600 depending on the rarity. My friend and former coworker Nathan Theriault has a nice side hustle via Instagram called Dumpster Dope that works on this model.

“Do you know the biggest shoe brand in the US and the second?” Dan asked me. “It’s Nike and then used Nikes.” The point he was trying to impress upon me was that the demand for luxury or limited products is enormous right now and thus collecting 2000 pounds of used clothing waste can be lucrative for Helpsy especially if that 2000 pounds contains 100 gems in the form of used Nikes, bras, Patagonia jackets, Armani suits, or a few Van Halen t-shirts. Dealing with the death of a parent or grandparent typically means cleaning out a house and what are you going to do with all that clothing? Donating it to a bin is usually the easiest thing to do.

However, luxury brands would rather have their items get incinerated in order to preserve the scarcity than enables their high prices. A secondary market for luxury goods is against the best interests of luxury brands because a used Burberry bag getting sold at a flea market benefits everyone involved except Burberry. Re-use is bad for clothing brands in terms of business, but it is the easiest and most sustainable thing we could do as consumers. That is why clothing brands typically try and market “sustainably sourced” or “recycled” raw materials in their messaging to get us to buy a new item.

I steered my conversation with Dan towards asking him if they are doing any secondary sorting operations for recycling of the raw materials into cotton or polyester bales. He told me they sometimes sell to recyclers and that the industry is growing, but the volumes that these recyclers can handle are not anywhere near what is needed. Helpsy is a relatively small company and they collect about 32 million pounds of clothing a year and just struck a deal with the city of Boston to deal with the unwanted clothing. Dan told me they are a small player trying to do good in the world and grow to be able to handle more. Being profitable corporation is important because the problem of clothing waste enormous.

As consumers we should think less about having the raw materials of our clothing recycled because as Dan told me, “When you’ve got a jacket that you don’t want, the most sustainable thing you can do is let someone else wear it. A lot of energy and labor went into making that jacket and to just shred it and recycle the fabric is just more energy being expended when someone else could just wear it.”

Recycling Finished Goods Back Into Raw Materials

Just like plastic and chemical companies the clothing that we do not want is an image problem for retailers. Just as chemical companies are viewing advanced recycling and compostable polymers as their coup de grâce for the plastic waste problem clothing companies are viewing recycling, upcycling, and advanced recycling as their solution.

When I was in graduate school there was some interesting coverage over this company that was making post consumer denim micarta. I couldn’t find the company’s website recently, but they were essentially taking old denim scraps, infusing them with epoxy resin and curing them into all sorts of interesting shapes for interior architectural applications. This was my first exposure to post-consumer clothing being used as a raw material. Another example would be Madewell who is using post-consumer denim for residential insulation batts.

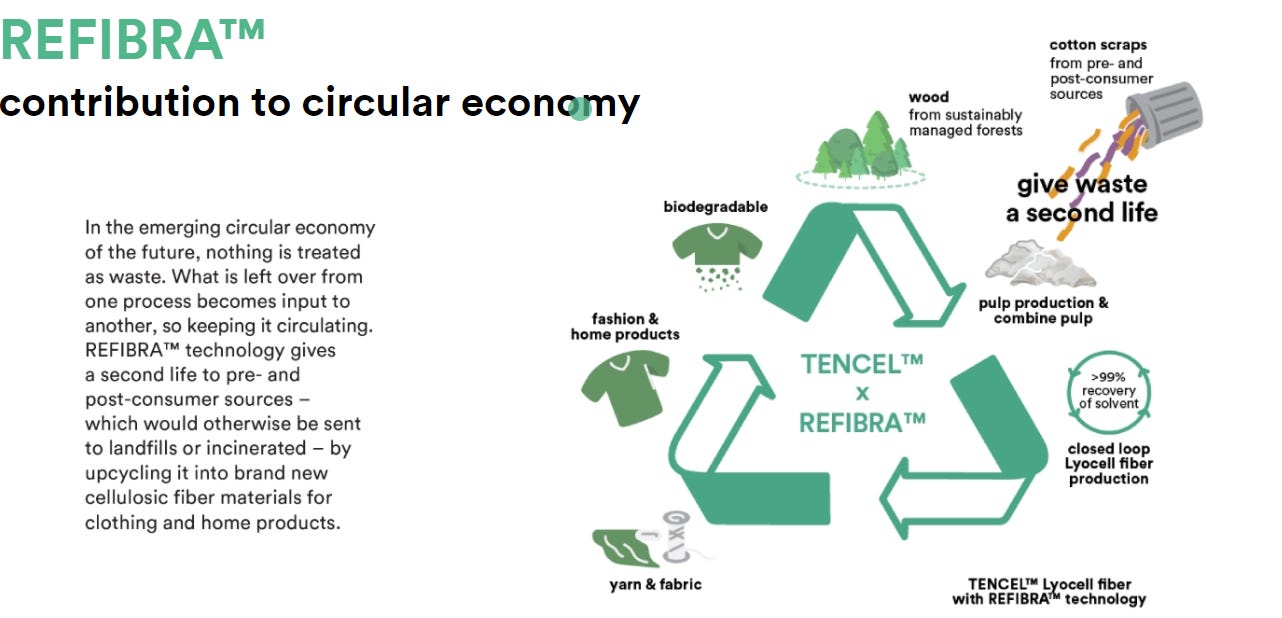

Cotton is just a biopolymer called cellulose and there are companies looking to turn waste into raw materials. Dan pointed me in the direction Renewcell, SMART, and Tencel to name a few. These companies are aiming to turn the corner and go fully circular in the production of clothing. Clothing brands are salivating over this concept because if they can source their raw materials from existing clothing then in a lot of ways they have achieved absolution or can at least claim it.

Tencel and Renewcell are taking Madewell’s idea of shredding cotton clothing and taking it a step further in that they want to make new cotton fiber from the pulp that is produced from used cotton clothing. One major issue here is that clothing waste needs to be sorted by material type prior to shredding and this costs a significant amount of money to do. Think about the picture of clothing bales further up the page and then sorting that clothing by type into cotton, nylon, and polyester. What about textiles with different percentages of natural and synthetic fibers, or buttons?

This is the same issue we have for plastic recycling but amplified.

A company between Helpsy and Tencel or Renewcell would need to do the sorting and they are probably only profitable if they have low cost labor or automation. Or costs for new virgin materials increases significantly while the price of recycled fabrics is less, but still enables profitability. There are some interesting public policy options that could happen here with respect to taxation and subsidy.

Companies like Renewcell or Tencel from what I can tell are able to run manufacturing operations on the scale of hundreds of thousands a pounds a day. Renewcell for instance announced in their 2020Q4 update that they had signed a 5 year deal with Tangshan Sanyou and would supply 40,000 metric tons of Circulose® pulp annually, beginning in the first half of 2022. This is all sounds great for cotton or cellulosic fabrics, but what about rayon, polyester, and Nylon?

For that, we will have to wait because this issue of the newsletter is already quite long.

In Conclusion of Part 1

There are really two things that are fueling the clothing waste problem:

Cheap labor that migrates to the lowest labor market and provides low cost raw materials in the form of natural and synthetic fabrics and finished goods means…

Low clothing costs for consumers, which makes clothing approach single use plastics territory. Plus, we get a nice dopamine response when we buy new clothing and when you can’t afford any other assets you might as well look good.

Think about the really expensive clothing you have in your closet. This is not disposable, but what separates that clothing from the cheap stuff you might buy at Target? The answer is probably somewhere around quality of the materials, quality of construction, and the brand. Another answer is because we collectively agree on the value of clothing much like we collectively agree on the value of money or Bitcoin. If enough people agree that a Birkin Bag should costs tens of thousands of dollars then it is less of a consumable item and more of an asset. My closet is a mixture of consumable items and quasi assets. The holes in my shirts might also just mean I’m wearing Yeezy Season 1.

Talk to you Friday,

Incredibly interesting, Tony. What an amazing read!

A colleague of mine made the point that part of the microplastic problem in the oceans is also driven by the activity of washing synthetic clothing. The breakdown of the fibers contributes to the very small particles getting into the water systems. It may be a different and more intractable problem to solve rather than the bulk deposition of plastics in the ocean but it will be a problem in the future.