The United States is NOT The Best at R&D

Why I'm bullish on the Europeans despite their current energy crisis

As an American I am as biased as any American is with the belief that their own country is exceptional and excels in everything. America—fuck yeah. Whenever I need to shake myself out of that mentality, I just re-watch the opening rant from Jeff Bridges in The Newsroom (the show is a bit cringe on a rewatch). This is his character having a mental breakdown on national television.

If I don’t have that clip handy, I just think about the fact that Evonik spent 10+ years on R&D into biosurfactants (rhamnolipids specifically). Evonik announced the start of production of biosurfactants from their plant in Slovakia in January 2024. Evonik is fermenting their biosurfactant, a molecule that is composed of a sugar and a fat that are chemically bound together. Sugar (water loving) and fats (water hating) do not like to mix and when they are bound together chemically, they tend to be able to act as an emulsifier or a surfactant due to their dual nature of both loving water and hating it. This means rhamnolipids could be used in personal care products, cleaning products, paint stabilizers, and in production of emulsified foods (soda syrups, creamy salad dressings, etc.). The market for surfactants is bigger than you might think, estimated to be worth about 66 billion in less than 10 years, and we use them every day. Evonik had this to say about Rhamnolipids:

Rhamnolipids are a class of biosurfactants that are sustainably manufactured via a fermentation process using European corn sugar as the main raw material. This biogenic, carbon-based process does not require petrochemical feedstocks or tropical oils. Rhamnolipids are fully biodegradable and offer a sustainable alternative to conventional surfactants due to their biobased raw materials, and low toxicological and ecotoxicological profile. Their exceptional foam-forming properties and mildness make them ideal for use in household cleaners and personal care products such as shampoos and micellar waters. They also offer superior performance for industrial applications such as coatings, mining and oil and gas.

This all sounds like an overnight success, but as all overnight successes, they take at least 10 years to occur. At my first American Chemical Society conference (2014) I saw a presentation from Oliver Thum about how Evonik could essentially produce rhamnolipids and their derivatives from just about anything, sugar, oil, butane, or whatever. In fact, when I saw that presentation Evonik had already been working in the space for 5-6 years (they publicly started in 2008). I’m writing this in 2024 and that means it has been 16 years of effort that might just now start to pay for itself.

Spending 10 years, let alone 16 years, on a R&D project without yielding profits would be unheard of in the United States chemical industry. We just do not have the patience (anymore) for waiting on scientists and engineers to figure out how to make that next big category defining product. Americans need that low hanging fruit so that they can funnel the extra cash flow into doing stock buybacks and paying out dividends. This newsletter focuses on the chemical industry (non-pharma) and according to McKinsey who credit this 2018 data from Capital IQ the industry is tiny compared to others such as pharma and medical products (why do you think I left?). Maybe $100 billion total if we count in some of the other industries too which are related.

Of the bit of money that does go into chemicals, agriculture, and materials, I suspect that those dollars are most effectively spent in Europe because there is a longer-term view that is forced on the industry. It’s more difficult to layoff 30% of your workforce in Europe than it is in the United States. It’s about 30-50% cheaper to hire a freshly minted PhD scientist in Europe and have them work on an interesting problem related to their thesis than it is in the United States. I think in a lot of ways it’s also probably easier to get a new chemical or polymer through the regulatory channels in Europe than it is here in the United States, especially if there is a benefit to improving the quality of life or reducing environmental burden. The rules of polymer exemption in Europe are a lot easier to meet than in the United States.

If you don’t buy my thesis on innovation slowing way down in the United States regarding new chemicals just look at the total PMN submissions and determinations by EPA since 2017.

It’s difficult to measure the success of innovation because it’s a marriage. Innovation is a marriage of science (technical possiblity), engineering (scaling that possibility up), and the current marketplace (generating profits). The first two are straight forward while the third is unpredictable and volatile. Further, the first two are not possible without the third. Essentially, chicken, egg, and chicken food—which comes first?

We have a lot of problems in the world generated by innovation and technological advances and pollution is probably the biggest problem. Other than becoming subsistence farmers and hunters and gatherers, the best way to solve the problem of pollution is a marriage of innovation and a functioning regulatory environment. The figure below is from the ACC, but the EPA’s own numbers on PMNs seems to also be directionally similar. In a country full of innovation and pushing the boundaries of what’s possible I’d expect the number of PMNs to be increasing or at least remaining flat over the last 7 years.

The EPA has a tough job. They get shit from both the industry and NGOs like Earth Justice. No one is happy with their work and it’s maybe some of the most important work that needs to be done in a timely manner. They simultaneously do not have enough authority and too much—Schrödinger’s Cat, move over.

After writing this newsletter for almost 3 years I’ve seen a lot of investment get poured into the European markets by both start-ups and big companies.

Eastman put their big bet (about a billion dollars) on polyester chemical recycling in France.

Avantium is building a big plant in the Netherlands to commercialize polyethylene furanoate.

Evonik is built their rhamnolipid plant in Slovakia (see above for details).

There are more examples out there and I encourage you to find them for yourself. I’ve written about many of them previously. Also, it’s not that I don’t think the US doesn’t innovate, we do, I don’t think we show the same urgency as Europe does. Perhaps this is due to being energy rich or just a lack of desire to climb up the tree and get all the fruit no one else can reach.

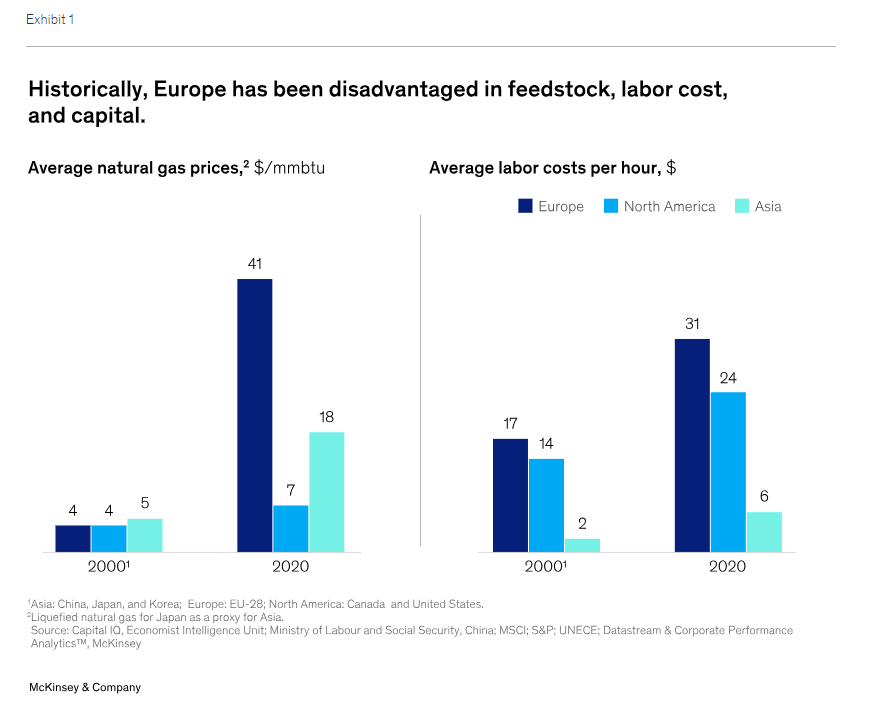

Based on the figure above I think Europe needs innovation more than we do here in the United States. It’s like your doctor telling you that you need to change your behavior because you have concerning blood pressure and cholesterol in your early 40s versus having triple bypass surgery after a massive heart attack in your 60s. When faced with impending doom you make changes and act in your own best interest and I think that is where the European chemical industry is right now.

While it might be cheaper to hire PhD scientists and engineers, it’s more expensive to run the plants and factories both in labor and the cost of energy. BASF has done big layoffs, moved energy intensive production out of Germany, and is changing the CEO.

I think we can do better here in the United States, but we need a breakout hit like a Tesla equivalent in chemical start-ups that also has some sort of sustainability aspect to create the fear of missing out. If I was going to bet (and I’m not), I’d bet on Origin Materials and Solugen being our Telsa here in the US for chemicals.

One or two success stories is all you need for a rocketship.

Let me know what you think in the comments.

Tony

Yeah, I know Elton isn’t singing about that kind of rocketship, but what a great version of this song.

And what's the point of a PMN when that's but one of 12+ international chemical inventory lists you have to register new chemicals on because many big players want global approvals upfront. Even if you have the money it's a hell of a time figuring out who to talk to or what forms to fill - and you'll need probably need to setup an only representative (maybe a really good distributor) at best or actual feet on the ground / an office in some countries.