Hey there,

This was actually two pieces I wrote in early 2021. I interviewed quite a few people for this including Dan Green of Helpsy, Romain Roux of Axens, and Vikram Nagargoje of Perpetual. This is long, but I think it’s worth it. I’ve tried to edit it a bit to be more streamlined, but I’m trying to take a break not create more work for myself. If you like this stuff consider sharing. With. Everyone. You. Know.

Free Trade, Offshoring, And Deflationary Pricing

A turning point in textiles in the United States happened when free trade opened up and light manufacturing left the United States for lower cost labor markets. Light manufacturing is classified as production of clothing, footwear, furniture, and other non-energy intensive goods. An old coworker of mine who is the quintessential Maine Shoe Dog grew up working in and with shoe factories. He used to tell me stories about when he was going to China, when most of the roads were undeveloped, to help get shoe factories started. He knew what a Hand Stitcher (someone who hand stitches shoes) could make in a year in Maine and he knows the few people left in Maine who can still do that job. He used to travel to China for years selling products into shoe factories, but he keeps himself busy these days with the shoe manufacturing that is left in North America. When people talk about lack of manufacturing jobs in the United States a significant portion of those jobs were light manufacturing.

If we fast forward to today a significant amount of light manufacturing such as shoe and apparel production are moving out of China, where labor has experienced significant wage growth. Light manufacturing is moving to other lower cost labor countries such as Vietnam, Myanmar, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and maybe eventually even Ethiopia. The consequences of this migration of labor is that the wages are incredibly low, but have the potential to rise in some countries such as Vietnam. There is a chance to replicate what happened in China in these new developing markets. Working conditions might be really bad in these countries, but these are the externalized costs we pay for $5 t-shirts. H&M is currently dealing with some of these externalized costs due to their contract manufacturing in Myanmar, a country which recently underwent a coup d'é·tat.

The concept of free trade was that it would enable lower costs for consumers in places like the US while providing better jobs to developing countries such as China. The consequences were that we reduced the number of manufacturing jobs here in the US and put the burden on people to educate themselves for jobs in the new knowledge economy. It eventually became critical to have a college degree or you were going to be left behind while minimum wage has not experienced any significant growth. Chris Rock’s joke on minimum wage from the perspective of an employer:

Hey if I could pay you less, I would, but it's against the law

Minimum wage isn’t what it used to be. My neighbors when I lived in Louisville, KY bought their house for $4,000 about 50 years ago and its easily worth about $200,000 today. This is about an 8% compound annual growth rate over 50 years. Wage growth has not kept constant with real estate prices or public company valuations. On the other hand clothing, footwear, and electronics have all seen significant reductions in price. This sets the stage for easy consumption of depreciating assets for many people, but appreciating assets become more difficult to acquire.

Here in the United States we just witnessed four years of a nationalist president who started a trade war with China. Some people argued that the trade war was needed to bring back manufacturing jobs to the United States (easier said than done) while others argued that this tough stance was essential for enforcement of intellectual property theft and to correct the trade deficit. In reality, globalization might matter less in the future as automation of production rises. Tilman Altenburg wrote about if light manufacturing would leave South East Asia for Ethiopia in 2019 for Brookings. It might, but I think it is more likely that automation takes over first. Some of the most advanced manufacturing techniques in the world are being developed in China and many of the factories in South East Asia are owned by Taiwanese companies.

Even if manufacturing were to relocate back to the United States it is not so simple as just supplying jobs. I’ll always remember drinking endless cups of tea in the only air conditioned room in a factory in Vietnam while the manager of the factory yelled at my coworker in Mandarin about our product quality. Meanwhile, in the US the quality of the products we produced was considered the best for the industry that was still remaining. Essentially, our quality was viewed as “shitty” by Chinese manufacturers, but the inverse was true for our domestic customers.

Even if you can get these jobs to people in the United States I am not sure how sustainable they are unless the wages are high enough at $15/hour or $31,200/year at 40 hours a week. Housing, healthcare, and transportation costs could easily eat a $15/hour salary for breakfast and still be hungry for more. Making T-shirts and shoes has some amount of danger involved. I’ve had owners of shoe brands trying to manufacture in the United States tell me that they can’t keep labor in their factories. The workers either quit because the job is too hard or they can’t stay off drugs. Higher wages are useful, but they are only useful if costs can be decreased.

Labor is really only one part of the equation here with respect to clothing. The second part of the equation we need to consider is the raw materials that go into the textiles. Our modern textiles are primarily made from natural fibers such as cotton, hemp, wool, and silk or from synthetic fibers such as polyester, spandex, and nylon. These fibers are all biopolymers or synthetic polymers (I did say I would bring this back to polymers). Synthetic fibers really took off with the invention of Nylon in the 1930s.

Synthetic Fabrics

Synthetic polymers enabled mass production of fabrics and materials that would help American Soldiers parachute in behind enemy lines during World War II due to having nylon parachutes. Prior to nylon the only way to make parachutes was from silk, which needed to be harvested from the silk worm and required an enormous amount of labor. This is an instance where substitution of silk by nylon created a whole new industry. An equivalent in today’s terms would be software that automates workflows, which is why companies like SAP and Salesforce are so powerful.

Azo Materials has a good comparison of the differences between nylon and silk. Nylon was able to do everything that silk was able to do, but making nylon was cheaper and was more resistant to growing mildew and other microorganisms. Nylon was not only cheaper to produce than silk, but it provided more value in specific applications like parachutes. Both silk and nylon belong to a class of polymers called polyamides.

If we want to make silk we have to have a farm that incubates silk worms and the cocoons of those silk worms is where the silk is harvested. This requires significant resources in terms of raising the silk worms and the harvesting of the cocoons. The same is true of cotton farms. You need vast amounts of viable land, water, pesticides, fertilizer, labor, and equipment to just harvest cotton. Then you need more machines and water to process that cotton into yarn.

Conversely, to make some nylon or polyester you need oil refinement and a downstream oil derivatives economy that currently exists and some chemical reactors. The allure of chemistry is that what works on the milligram scale usually works at multiples of tons. The labor required to make 16 tons of nylon or polyester in a day is the same as 1 ton and the pricing of the raw materials becomes more favorable at larger scales due to favorable labor costs. Further these economies of scale became established in the 1940s and I’ve just recapped the nylon problem again. Get some chemical engineers to work at optimizing the process and eventually you can make a synthetic fiber with less raw material and land requirements than natural fibers and the process trends towards efficiency provided that the equipment is maintained. The capital expenditures might be higher be at first for synthetics, but over 10-20 years of production combined with depreciation of assets means that making nylon and polyester fibers is a great business as long as someone is buying your fiber.

But wait, there is even more value here for synthetics.

Synthetic polymers enable either mimicry of traditional fabrics and impart increased value in the form of new properties such as elasticity or breathability. There is no Lulu Lemon without Spandex, a polyurethane. There are no fire resistant suits for firefighters without Nomex, a polyaramide. There are no high performance ski jackets without GoreTex, microporous polytetrafluoroethylene. There are no Nikes without synthetic fabrics, rubber, polymeric foams, and synthetic adhesives. Prior to synthetic fabrics the best you could do if you got caught out in the rain was a rubber poncho or maybe waxed cotton while these days you could carry a rain jacket in your pocket.

Synthetic fabrics might feel like silk, soft cotton, or leather, but they can provide more value due to polymer chemists and engineers manipulating the end properties of those fabrics in a lab. There are no $15 dollar fast fashion garments without polyester and cheap labor producing cotton with minimal environmental standards in developing countries. The combination of low cost labor and low cost raw materials means we can buy new clothing every year and landfill that clothing when they start to look a little worn. Patagonia does a pretty good job outlining this on their website.

The combination of cheap labor and raw materials have resulted in the viewpoint that clothing might last us a few years and then they can be thrown away. We are a few steps away from treating our clothing like single use plastics. Many single use plastics can actually be used multiple times, but because the costs are so low we view them as disposable. Clothing brands are kind of like chemical companies here in that they believe it is the consumer who needs to reconcile these issues.

Clothes Are Not Trash

In trying to understand more about our clothing waste problem I recently spoke to Dan Green, the co-founder of Helpsy. Our conversation was too long to publish here, but he helped open my eyes to the clothing waste problem. Dan told me that the typical American generates about 100 pounds of clothing waste a year, 85% of our clothing waste goes to landfills or gets incinerated while the remaining 15% gets diverted. Of that 15% only about a quarter of it gets sold on secondary markets and the rest gets sent to developing countries such as Pakistan. That means in the US we generate somewhere close to 30 billion pounds of clothing waste every year. In the developing countries that clothing is either re-used or cut into rags. Synthetic fabrics make terrible rags so those get thrown in the trash.

Helpsy is primarily concerned about collecting unwanted clothing and trying to find a better place for them. They are a reverse logistics company in that they deal with waste as opposed to raw materials or finished goods. In their open letter to consumers Helpsy tells us:

Here are the facts: the only way recycling at necessary scale will happen is by for-profit recycling and reverse logistics companies, these companies primarily operate through bins. They afford the hefty cost of collection directly through the value of the goods collected, full-stop. Any type of recycling is a commodity-based and market-driven business. Just as in the traditional recycling industry (plastic/glass/paper), the value of the goods collected [is] in the value of the most sellable materials. Think of it this way: we can’t recycle your ripped towels if we don’t also get your Nikes. As businesses we might be able to handle damaged or defective clothing items but can only afford to do so based on the best, most reusable & recyclable items we receive.

Companies like Helpsy make money and pay their employees and shareholders much in the way of being a gold prospector. They have a massive amount of raw material that could contain “gems” and the finding and selling of those gems is what also enables them to recycle the ripped and stained underwear. A gem is a colloquial term that thrifters or pickers call rare items such as Van Halen tour t-shirts, a Burberry bag, or limited edition Nike shoes from 1995. These gems can be flipped on the internet anywhere between $200-600 depending on the rarity. My friend and former coworker Nathan Theriault has a nice side hustle via Instagram called Dumpster Dope that works on this model.

“Do you know the biggest shoe brand in the US and the second?” Dan asked me. “It’s Nike and then used Nikes.” The point he was trying to impress upon me was that the demand for luxury or limited products is enormous right now and thus collecting 2000 pounds of used clothing waste can be lucrative for Helpsy especially if that 2000 pounds contains 100 gems in the form of used Nikes, bras, Patagonia jackets, Armani suits, or a few Van Halen t-shirts. Dealing with the death of a parent or grandparent typically means cleaning out a house and what are you going to do with all that clothing? Donating it to a bin is usually the easiest thing to do.

However, luxury brands would rather have their items get incinerated in order to preserve the scarcity than enables their high prices. A secondary market for luxury goods is against the best interests of luxury brands because a used Burberry bag getting sold at a flea market benefits everyone involved except Burberry. Re-use is bad for clothing brands in terms of business, but it is the easiest and most sustainable thing we could do as consumers. That is why clothing brands typically try and market “sustainably sourced” or “recycled” raw materials in their messaging to get us to buy a new item.

I steered my conversation with Dan towards asking him if they are doing any secondary sorting operations for recycling of the raw materials into cotton or polyester bales. He told me they sometimes sell to recyclers and that the industry is growing, but the volumes that these recyclers can handle are not anywhere near what is needed. Helpsy is a relatively small company and they collect about 32 million pounds of clothing a year and just struck a deal with the city of Boston to deal with the unwanted clothing. Dan told me they are a small player trying to do good in the world and grow to be able to handle more. Being profitable corporation is important because the problem of clothing waste enormous.

As consumers we should think less about having the raw materials of our clothing recycled because as Dan told me, “When you’ve got a jacket that you don’t want, the most sustainable thing you can do is let someone else wear it. A lot of energy and labor went into making that jacket and to just shred it and recycle the fabric is just more energy being expended when someone else could just wear it.”

Recycling Finished Goods Back Into Raw Materials

Just like plastic and chemical companies the clothing that we do not want is an image problem for retailers. Just as chemical companies are viewing advanced recycling and compostable polymers as their coup de grâce for the plastic waste problem clothing companies are viewing recycling, upcycling, and advanced recycling as their solution.

When I was in graduate school there was some interesting coverage over this company that was making post consumer denim micarta. I couldn’t find the company’s website recently, but they were essentially taking old denim scraps, infusing them with epoxy resin and curing them into all sorts of interesting shapes for interior architectural applications. This was my first exposure to post-consumer clothing being used as a raw material. Another example would be Madewell who is using post-consumer denim for residential insulation batts.

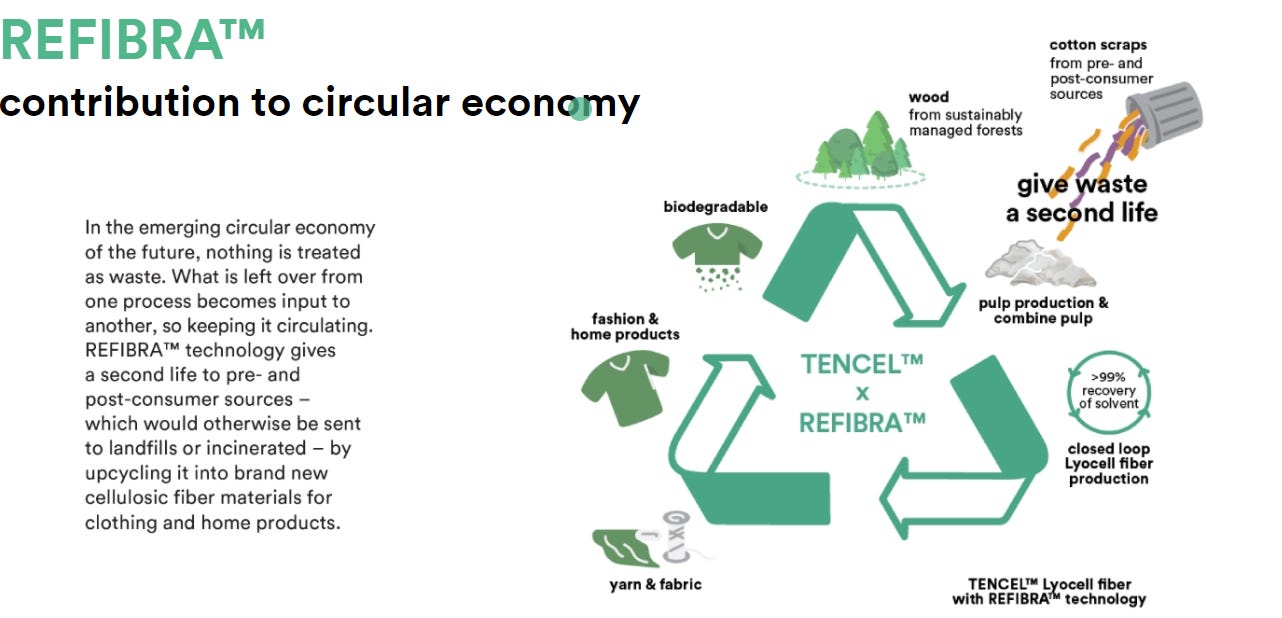

Cotton is just a biopolymer called cellulose and there are companies looking to turn waste into raw materials. Dan pointed me in the direction Renewcell, SMART, and Tencel to name a few. These companies are aiming to turn the corner and go fully circular in the production of clothing. Clothing brands are salivating over this concept because if they can source their raw materials from existing clothing then in a lot of ways they have achieved absolution or can at least claim it.

Tencel and Renewcell are taking Madewell’s idea of shredding cotton clothing and taking it a step further in that they want to make new cotton fiber from the pulp that is produced from used cotton clothing. One major issue here is that clothing waste needs to be sorted by material type prior to shredding and this costs a significant amount of money to do. Think about the picture of clothing bales further up the page and then sorting that clothing by type into cotton, nylon, and polyester. What about textiles with different percentages of natural and synthetic fibers, or buttons?

This is the same issue we have for plastic recycling but amplified.

A company between Helpsy and Tencel or Renewcell would need to do the sorting and they are probably only profitable if they have low cost labor or automation. Or costs for new virgin materials increases significantly while the price of recycled fabrics is less, but still enables profitability. There are some interesting public policy options that could happen here with respect to taxation and subsidy.

Companies like Renewcell or Tencel from what I can tell are able to run manufacturing operations on the scale of hundreds of thousands a pounds a day. Renewcell for instance announced in their 2020Q4 update that they had signed a 5 year deal with Tangshan Sanyou and would supply 40,000 metric tons of Circulose® pulp annually, beginning in the first half of 2022. This is all sounds great for cotton or cellulosic fabrics, but what about rayon, polyester, and Nylon?

I’ve noticed a lot of consternation amongst people around microfibers getting into the oceans and much of the blame is on synthetic fabrics. Mark Hillsdon wrote an excellent article for Reuters on the issue of microfabrics being pushed into our oceans from washing clothing.

Although around 50% of our clothing is made from plastic, new research from Italy’s Institute of Marine Sciences suggests that the majority of these tiny threads aren’t made of synthetic fabrics such as polyester and nylon, as had been presumed, but cotton, linen and other man-made fibres such as rayon, which have been so impregnated with chemicals that they aren’t able to naturally biodegrade.

That’s right, the plastic that holds your juice or soda or iced coffee is the same plastic that goes into the synthetic fabrics that we wear. Polyester or PET is the carpets that we install in our houses, hotels, and businesses and it’s the Patagonia and North Face fleece jackets we wear on a cold day. Polymer chemists and engineers have also already started figuring out how to repurpose our clothing waste back into raw materials to produce new clothing. In the first half of this series I wrote about cellulose or cotton fabrics being repurposed, but this week I want to focus on the big synthetic fabric polyester or as I know it, polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

Companies Trying To Make A Circular Clothing Economy

Jeplan and Axens

Two companies came onto my radar recently that are looking to solve the clothing waste problem, much in the way that Helpsy is attempting to collect unwanted clothing. The first is actually a partnership between Jeplan and Axens. Jeplan is trying to take polyester clothing and turn it back into fibers to make new clothing. Per Jeplan’s website:

We developed the “clothing-to-clothing” BRING Technology™ as a technology allowing manufactured products to be put back into circulation rather than thrown away. Further, BRING Technology™ clothing can be recycled any number of times, making polyester a sustainable resource rather than an environmental burden. We hope this will fundamentally change methods for manufacturing and attitudes toward it in the fashion industry.

We will return dreams and hopes to the fashion world by creating a future where BRING Technology™ reduces the amount of clothing that is thrown away, allowing us to truly enjoy fashion.

Axens is the French chemical technology company that has partnered with Jeplan, a reverse logistics company, to bring the dream of chemical recycling of polyester clothing back into clothing a reality. Because Axen’s technology can turn polyester clothing back into clothing it can also turn other polyesters such as those from bottles or packaging into the filaments that make up polyester textiles as well. Axens is similar to Agilyx or Johnson Matthey in that they have chemical technologies that can be licensed to other companies. I spoke with Romain Roux, an adviser to the Chief Technology Officer and Fabian Lambert the Technology Development Manager recently about their efforts on doing chemical recycling of plastics.

There has been some significant debate over the past few months about chemical recycling of plastics versus mechanical recycling. I think I covered some of the issues in a previous newsletter issue when I wrote about Eastman’s methanolysis plant. The plastic waste problem and clothing waste problems are so big that any additional solutions that can take some volume of the waste is a good thing. If these additional waste solutions can become profitable businesses by producing high quality products that the broader market wants then we could have a virtuous economic cycle around treating our waste like a valuable raw material.

Romain was clear with me in that he believes that if plastic can be mechanically recycled then it should be as it is a cost and energy efficient process, but often mechanical recycling is not an option. Typically only high quality separated plastic waste such as single stream PET or HDPE have the potential to get mechanically recycled. Separation and having a market for the big six plastics (HDPE, LDPE, PP, PVC, PS, and PET) will overall make it easier for mechanical and chemical recyclers alike to process more spent plastics.

Axens has three technologies available for chemical recycling of plastics. The first two involve conversion of mixed plastics into either naphtha, which is similar to an oil distillate used to make plastics or pyrolysis of mixed plastic to an oil which can be turned into naphtha. Both processes are seeking to make naphtha, which is what oil companies want to make chemicals and fuels. Naphtha is important because it can either be steam cracked to make olefins and platform chemicals or it can be used to make fuel. Having the ability to turn naphtha into whichever the market demands is a nice flexibility to have when dealing with plastic waste no one wants.

Axen’s third process is a chemical depolymerization of PET with ethylene glycol. PET or polyester made by polymerization of terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol and modern processes are done through making what is known as BHET or Bis(2-Hydroxyethyl) terephthalate as the chemists say (we actually just say BHET). BHET is like an intermediate product of terephthalic acid reacting with two ethylene glycols and then with further heating and vacuum ethylene glycol can be removed and PET is produced. Because many chemical reactions are reversible Axen’s depolymerization process involves putting that ethylene glycol back with PET and cooking it to yield BHET in a soup of ethylene glycol (ethylene glycol is essentially antifreeze). This depolymerization can further enable the purification of the polyester from whatever color it may have possessed to make clear or natural colored polyester that can then be used to make new clothing.

Glycolysis has a few advantages over methanolysis such as being able to be carried out at much higher temperatures under normal pressures, which can help speed up the depolymerization process, and there is no need to handle methanol, which can present a flammability problem. The ethylene glycol produced from the repolymerization of BHET obtained by Axen’s process can then be recycled back and used to depolymerize the next batch in a continuous or semi-continuous process.

Axens is currently working with Jeplan to retrofit and reopen Jeplan’s PET recycling plant with their technology. The goal of Jeplan is to produce clothing quality PET fiber from polyester clothing and packaging. A true circular cycle if the supply chain and economic models can be figured out. Japan also represents an excellent model for the reverse logistics that need to happen to execute in terms of unwanted clothing collection, sorting, and having the raw material produced from the process be valued at a higher price point compared to PET fiber produced from oil.

Perpetual

Axens and Jeplan are not the only ones doing glycolysis of polyethylene terephthalate to turn plastic and clothing waste into new textiles. I came across PerPETual by bumping into Vikram Nagargoje in a LinkedIn comments section. We talked for over an hour about plastics recycling, the future that he sees in the space of PET glycolysis, and the challenges of running an advanced plastics recycling company.

Perpetual’s goal is to take PET bottles and turn them into polyester filament yarns. All synthetic fabrics start from filament yarns and these yarns are what make a synthetic textile either by weaving or knitting. Rolls of fabric can then be cut into a pattern, stitched, and then it becomes a t-shirt, an upper for a pair of Nike Flyknits, or a jacket. The idea that a Diet Coke bottle can be part of the T-shirt that I am wearing now was somewhat radical a few years ago, but now I think it is our future.

Vikram told me that Perpetual’s glycolysis process is continuous and uses the least amount of ethylene glycol compared to their competition. This enables them to take clear PET flakes from a recycler and turn it into a depolymerized intermediate composition consisting of polyester oligomers, BHET, and some glycol. He showed it to me on camera and it looked a bit like a white hockey puck that he was able to break apart in his hands.

The big difference between what Perpetual and Axens is doing is the amount of glycol used in the process and this in turn influences the raw materials that they can input into their processes. Vikram told me that their process of turning PET bottles into fibers is highly dependent on high quality PET bales that they buy from recyclers. They can often achieve 80% yields of PET waste to fiber, which is quite good, but if there are too many impurities it can lead to fibers breaking during production. Fiber breaks lead to downtime in manufacturing and downtime means less profitability. Ultimately, what can determine profitability for a factory is productivity. From what I can tell the Axens process is much more flexible on some raw material impurities due to the higher glycol content and better potential to filter out contaminants, which is why they can process recycled PET packaging and polyester clothing.

Vikram told me that the quality of recycled PET from India and Europe is significantly better than other countries. Buying recycled PET from the US just isn’t economical due to the impurities, which lead to low yields and constant stoppage of production. If the United States were to get serious about recycling post consumer PET then we would need to become more serious about making those waste streams have higher purity and secondary sorting.

We also spent some time talking about the economics of advanced recycling and another reason why being in India is economical for his company. Perpetual can buy high quality polyester bottles for $500 per ton while similar quality recycled PET in Asia or Europe will be 20-30% higher in cost. Perpetual can then get those bottles flaked and into their process where they can produce polyester fibers at 600 feet per minute with a 70-75 denier strength. Sportswear brands that use a lot of polyester in their clothing like Nike, Decathlon, and The North Face, are all either interested in buying Perpetual’s fibers or are currently using them in their process. Perpetual is sold out on volume until the end of 2022 for their products and is having trouble meeting demand. These are good problems to have.

Perpetual was cash flow positive when we talked and at the time Vikram was looking to expand capacity due to his slowly growing, but profitable business. If successful, I think Perpetual could quietly lead the world with their advanced recycling efforts.

Note: At the time of my writing this India had been doing relatively well during the pandemic. The pandemic is currently wreaking havoc in India. Here is an article from VOX and one from the New York Times on how you might be able to help if you are so inclined.

Conclusion

Pairing a company like Perpetual with other reverse logistics companies such as Helpsy or Jeplan to turn what we thought was trash into something useful is the future. The fact that this is happening in India and is profitable indicates that there are some significant opportunities in developing countries to leapfrog the paths that countries like England and the United States took. These more sustainable opportunities could be used by these countries to forge their own sustainable futures and lead the way where developing countries are struggling to even collect recyclable materials.