An Ace Up Your Sleeve

Why it's a good idea to have one and how to get it.

I haven’t quite published at the cadence that I would have hoped in 2025, but I did put out roughly 8 things that I thought were useful. If I were to put a floor on what a productive amount coming out of this newsletter would be—it would be about 4 original pieces from me in a year that a CEO could email to his whole company and say something like, “We need to read this and think about it.” I only use this as an example because multiple CEOs of chemical companies have told me they have done this and considering this could happen I’d want it to be something useful and that could withstand the tests of time. I’m hoping to be writing this thing for a long time.

Pulling a $100 million idea out of “nowhere,” especially when you really need one to survive to the next quarter or the next year is something every chemical company should be able to do either as a start-up or a big established company. The ability to have an “ace up your sleeve” today started five years ago in the lab on some crazy idea that shareholders or board members wouldn’t want to hear about spending a penny on much less a few million dollars and five years of time. Ultimately, the CEO or President of the company needs to have enough courage to be enabling this type of “wasteful behavior” so that their business can build the processes, teams, and the trust it takes to deliver of culture of innovation that not only maintains the current business but can create ideas worth spinning off that ultimately benefit shareholders.

An Ace Up Your Sleeve

People like to draw similarities between business and poker because you have to make big monetary decisions with limited information. If you got caught in any poker game in the country with the Ace of Spades hiding up your sleeve you’d at a minimum thrown out and banned from the establishment. Having an ace up your sleeve as a start-up or an established business that you can play when your luck is drying up would probably be called a good strategy.

The problem with modern research and development, at least in the industrials sector, is that it’s really disguised as technical service to existing products and customers. The R&D scientist gets called up to the plant when a batch has gone sideways or a customer is complaining that the glue isn’t sticking anymore (hint: it’s almost never the glue’s fault. It is the mold release agent on the part). That same R&D scientist wasn’t working on some big breakthrough project prior to dealing with a customer complaint or a production issue. That scientist was probably trying to make a marginally better product either with respect to cost efficiency to drive overall profits/EBITA or marginally better value to either maintain or gain additional volume in the marketplace.

The whole strategy of having an ace up your sleeve makes sense, but it can be the difference between success and bankruptcy for small companies. When I first wrote about Origin Materials it was all about converting wood chips to furan intermediates and then conversion of those furanics to chemicals that could be used to make terephthalic acid or a fully bio-based route to poly(ethylene terephthalate) or PET. Things for Origin were looking great at the time from the initial build out of the pilot/demonstration plant to starting construction on the bigger plant (O2) in Louisiana. Things started to falter a bit and Origin really needed a path to profitability and an ability to become self-sustaining due to being public. This is when they played their 100% PET cap and closure card. Origin announced in November of 2024 a new round of debt financing and a path to revenue growth off their caps business:

2026: Revenue of $20 million to $30 million.

2027: Revenue of $100 million to $200 million.

Adjusted EBITDA run-rate breakeven: 2027.

The original thing that Origin was working on was not making a fully finished 100% PET cap/closure system for water bottles. The main strategy and plan of Origin was to make chemicals to sell to other chemical companies to make PET. If a company want to pull a potential giant revenue business out of what seems like thin air then you need to have the right research and development programs running and these programs need the right amount of support (hint: it’s not 50% of a single marketing manager’s time).

You might be thinking that this seems like the most obvious thing in the world. Your company’s R&D programs should be constantly running things in the background so you can commercialize new discoveries and make a billion dollars. The problem is that this is often not the case because the budget of R&D have been scrutinized, pinched, and squeezed for the last 20+ years. Often, what is left is a team that can try and move the needle on innovation just enough to eke out a few tenths of a percent of growth by the end of the year. This squeeze on innovation is what has allowed startups to actually start to gain some traction (see Origin Materials above). A 100% PET cap and closure system probably should have been developed and brought to market by an incumbent, but for whatever reason this never happened.

The Current Private Equity Model Is Not the Answer

The over financialization of chemicals and materials has thwarted the entire reason the business was somewhat successful in the first place. We are starving for technical innovation. The private equity model has been employed throughout the chemical industry not just in mergers and acquisitions among private chemical companies, often owned by private equity funds (e.g., Apollo, KKR, Standard Industries), but in public chemical companies as well. DuPont has essentially been trying to use a playbook of rolling up high profit companies to make a speciality chemical company pure play, but it has fractured further in 2025. DuPont sold their Kevlar business for $1.8 billion with Nomex to be sold next. The DuPont board approved the spinoff of their electronics business (Qnity) after they spent the past few years rolling up electronics materials companies and touting themselves as a real speciality chemicals company when they split off from DowDupont. DuPont’s CEO, Lori Koch, does not have a background in manufacturing or chemicals, but comes from the finance world. Needless to say, I think the performance of DuPont has been disappointing.

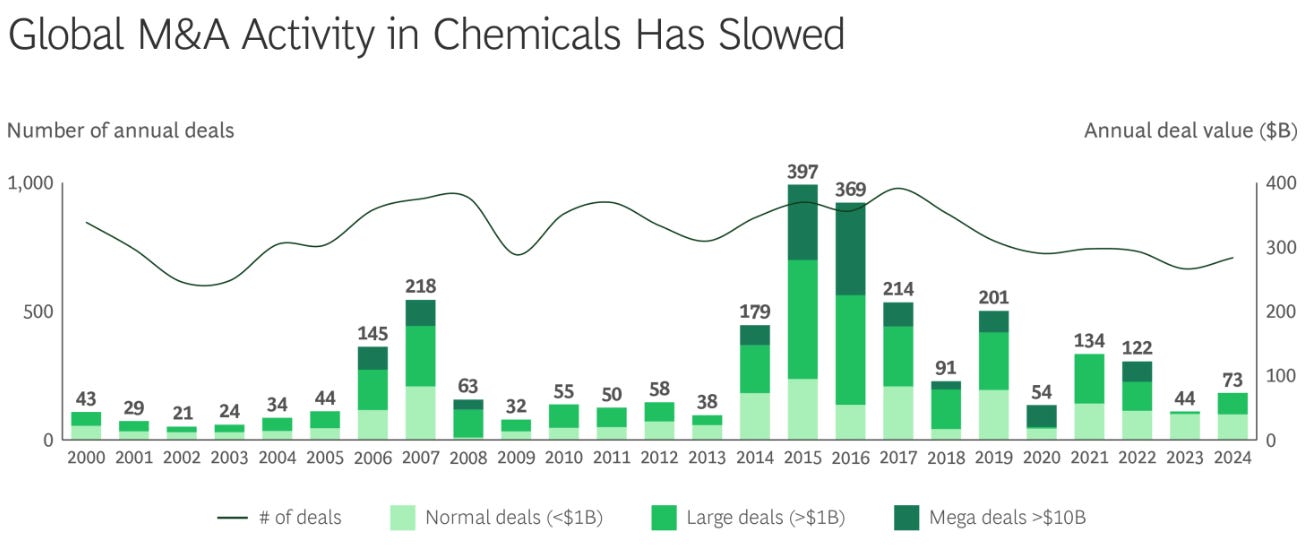

Private equity returns over the last few years have also been lackluster. This underperformance to the broader stock market could have been impacting the overall global M&A in chemicals.

Boston Consulting Group’s analysis of the lack of deal flow (when compared to 2014-2019) provides an analysis on the current driver of deals in the marketplace. “[Chemical companies are focusing] on smaller, more specialized acquisitions and growth opportunities in adjacent markets, portfolio optimization and diversification and technology and innovation have gained in importance as deal rationales.”

Innovation has supposedly gained importance. To me, this is a potential early indicator that access to people who have the facilities to even attempt innovation is potentially viewed as important or maybe this is just a nice thing to write to get you to buy BCG’s services. In my experience the established companies love to signal that “innovation is important,” to the public and investors, but internally will then follow-up this concept with “being thoughtful” or “prioritizing easy to commercialize projects.” Essentially, a CEO might state that innovation and R&D are core to the business, but then may proceed to cut investment into R&D a few quarters later. Perhaps, I’ve just been in the wrong place at the wrong time too often and I’m jaded.

The Problem With Innovation

To me, this all means that chemical company leadership teams know that new products and innovation that are patentable and bring real value to customers is important. A fundamental lack of understanding in how these things are created and brought to the market is quite normal. I think there is plenty of experience in launching Product A, but with a “+” next to the name. There are not that many people who are experienced with bringing something completely new to the world. For example, if an R&D team brings 10 ideas to a level of being able to send samples to customers and gain feedback but then decide to not commercialize anything because the business wouldn’t be profitable is a sign of extreme success. Not only can the team execute on new ideas, but they have the discipline to shelve them when they do not work.

The problem with real innovation and successful commercialization is that it takes longer than anyone wants to admit. It might have taken DuPont 10+ years to invent and commercialize the technology behind Kevlar and Nomex, but they sold one aspect of that business for $1.8 billion not to mention the last 20+ years of harvesting profits from operating the business from what appeared to be with almost no actual competition until relatively late in the business cycle. DuPont launched Kevlar in 1971 and their main competitor, Teijin Aramid, launched their para-aramid product in the 1990s after a patent dispute in the 1980s. DuPont had almost 20 years of exclusive global Kevlar sales and marketing available to them until a single competitor came to get them. The third competitor, Kolon, wouldn’t show up until 2005. The seeds of innovation that are planted today take time to yield results and when they do they are worth billions. Further, in a world of bits versus atoms, the atoms tend to be the most enduring businesses once established.

Picking “innovation” winners early and signaling to your investors just isn’t possible. I suspect that investors who are about to give an executive team $250 million to finance the construction of a new chemical plant want more assurances than “no one really knows how much we will make here.” This is when people start to make up numbers based on limited information and will decide that five “innovation” projects will yield $5 billion dollars in 15 years. There’s a couple of nice aspect to that statement for an executive team:

$X billion is big enough to make just about anyone really eager to get in a deal

15 years is long enough to where if I don’t deliver then I’ll probably be close to retirement anyway and it will not matter much

Alternatively, maybe something happens and it’s not your fault it didn’t work out because new information came to light 8 years later and it’s just not possible anymore.

While these statements are nice for the executive team, it’s the scientists, engineers, and sales people who need to deliver on those billion dollar promises. Sometimes, these promises are impossible and often the teams trying to keep to a specific goal and timeline will ultimately be blamed and then get laid off or fired. The flip side of success is that maybe a few become part of the senior leadership team, but most will be told they are “just doing their job.” Even if they are successful they might still get laid off to make the business even more profitable prior to a sale to a competitor or someone who wants to overpay (i.e., private equity). This makes scientists and engineers (especially those who are early in their career) prone to jumping ship before they get axed. This means the best and brightest move on to different opportunities and the executive team are left holding the bag of low/no growth.

Dealing Yourself An Ace

Ultimately, it’s the senior leadership of a company who are responsible on delivering innovation. In the case of a start-up the senior leader is often the inventor. Hopefully, they aren’t an asshole who rules their organization through fear, but leads others despite their own fears and insecurities. Board members and executives of established companies should hopefully know that a few percentages of revenue should be used efficiently and that teams can both maintain existing products while also taking big swings and misses at the same time. Having visibility into how products are made and commercialized is a real super power and shielding teams from activist shareholders who just want more money today through cost cutting is one of the most important jobs of an executive team.

I’ve seen a lot of models of innovation at larger companies where the R&D directors don’t want to know about your “free time experiments.” The reasoning here is that if they don’t know you just wasted a bunch of time on something that didn’t work then they don’t have to report up their management chain that you failed in the lab to make something cool and new. There is no real incentive here for anyone to succeed if things are just “kept quiet.” At a minimum, an R&D director or VP of technology or the most technically skilled/gifted person in an organization should be capable of mentoring and coaching younger scientists and engineers in delivering on innovation.

Ultimately, innovation comes through in cultures where it is fostered. There’s plenty of literature and books out there that will tell you open labs and basic research are key to success. I agree that some basic research is useful, but there is nothing like being out in the field as a scientist working a product line with an operator or at a job site with customer and understanding the limits that a product might be subjected to when trying to think of new and better ideas. Scientists and engineers need to be able to collaborate with absolute trust with their commercial teams and operations teams and if something fails to commercialize then it’s just the cost of doing business.

You think a card mechanic can just deal themselves cards off the bottom of the deck without practicing and failing a lot? I guarantee you they failed a lot before they did it flawlessly.

The same is true in delivering real innovation in chemicals and materials science. Failure is just practicing until you get it right.